Welcome to Smartindia Student's Blogall posts

humayuns tomb

Humayun's tomb (Urdu: ?????? ?? ?????? Humayun ka Maqbara) is the tomb of the Mughal Emperor Humayun. The tomb was commissioned by Humayun's first wife Bega Begum (Haji Begum)[1][2][3][4][5][6] in 1569-70, and designed by Mirak Mirza Ghiyas, a Persian architect chosen by Bega Begum.[7][8] It was the first garden-tomb on the Indian subcontinent,[9] and is located in Nizamuddin East, Delhi, India, close to the Dina-panah citadel also known as Purana Qila (Old Fort), that Humayun founded in 1533. It was also the first structure to use red sandstone at such a scale[10][11] The tomb was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993,[9] and since then has undergone extensive restoration work, which is complete.[12] Besides the main tomb enclosure of Humayun, several smaller monuments dot the pathway leading up to it, from the main entrance in the West, including one that even pre-dates the main tomb itself, by twenty years; it is the tomb complex of Isa Khan Niyazi, an Afghan noble in Sher Shah Suri's court of the Suri dynasty, who fought

parliment house

The Parliament of India, also popularly known as Sansad (Sanskrit: ????); is the supreme legislative body in India. The Parliament comprises the President of India and the two Houses—Lok Sabha (House of the People) and Rajya Sabha (Council of States). The President has the power to summon and prorogue either House of Parliament or to dissolve Lok Sabha.[5]

India's is bicameral; Rajya Sabha is the upper house and Lok Sabha is the lower house. The two Houses meet in separate chambers in theSansad Bhavan (located on the Sansad Marg or "Parliament Street") in New Delhi. Those elected or nominated (by the President) to either house of Parliament are referred to as Members of Parliament or MPs. The MPs of Lok Sabha are directly elected by the Indian public and the MPs of Rajya Sabha are elected by the members of the State Legislative Assemblies, in accordance with proportional representation. The Parliament is composed of 790 MPs, who serve the largest democratic electorate in the world; 714 million Indians registered to vote in the 2009 general elections.

penguin

| Penguins Temporal range: Paleocene-Recent, 62–0Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Gentoo Penguin, Pygoscelis papua | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Infraclass: | Neognathae |

| Order: | Sphenisciformes Sharpe, 1891 |

| Family: | Spheniscidae Bonaparte, 1831 |

| |

| Range of Penguins, all species (aqua) Aptenodytes | |

Penguins (order Sphenisciformes, family Spheniscidae) are a group of aquatic, flightless birds living almost exclusively in the southern hemisphere, especially in Antarctica. Highly adapted for life in the water, penguins have countershaded dark and white plumage, and their wings have evolved into flippers. Most penguins feed on krill, fish, squid and other forms of sealife caught while swimming underwater. They spend about half of their lives on land and half in the oceans.

Although all penguin species are native to the southern hemisphere, they are not found only in cold climates, such as Antarctica. In fact, only a few species of penguin live so far south. Several species are found in the temperate zone, and one species, the Galápagos Penguin, lives near the equator.

The largest living species is the Emperor Penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri): on average adults are about 1.1 m (3 ft 7 in) tall and weigh 35 kg (75 lb) or more. The smallest penguin species is the Little Blue Penguin (Eudyptula minor), also known as the Fairy Penguin, which stands around 40 cm tall (16 in) and weighs 1 kg (2.2 lb). Among extant penguins, larger penguins inhabit colder regions, while smaller penguins are generally found in temperate or even tropical climates (see also Bergmann's Rule). Some prehistoric species attained enormous sizes, becoming as tall or as heavy as an adult human. These were not restricted to Antarctic regions; on the contrary, subantarctic regions harboured high diversity, and at least one giant penguin occurred in a region not quite 2,000 km south of the equator 35 mya, in a climate decidedly warmer than today.

Contents[hide] |

Etymology

The word "Penguin" first appears in the 16th century as a synonym for Great Auk.[1] It may be derived from the Welsh pen gwyn "white head", although the etymology is debated. When European explorers discovered what are today known as penguins in the Southern Hemisphere, they noticed their similar appearance to the Great Auk of the northern hemisphere, and named them after this bird, although they are not related.[2]

The etymology of the word "penguin" is still debated. The English word is not apparently of French,[1] nor of Breton[3] or Spanish[4] origin (both attributed to the French word pingouin "auk"), but first appears in English or Dutch.[1]

Some dictionaries suggest a derivation from Welsh pen, "head" and gwyn, "white", including the Oxford English Dictionary,[5] the American Heritage Dictionary,[6] the Century Dictionary[7] and Merriam-Webster,[8] on the basis that the name was originally applied to the great auk, either because it was found on White Head Island (Welsh Pen Gwyn) in Newfoundland, or because it had white circles around its eyes (though the head was black).

An alternative etymology links the word to Latin pinguis which means "fat". In Dutch the alternative word for penguin is 'fat-goose' ('vetgans' see: Dutch wiki or dictionaries under Pinguïn), and would indicate this bird received its name from its appearance.

Systematics and evolution

Living species and recent extinctions

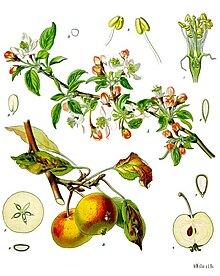

apple

pple

| Apple | |

|---|---|

| |

| A typical apple | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Rosaceae |

| Genus: | Malus |

| Species: | M. domestica |

| Binomial name | |

| Malus domestica Borkh., 1803 | |

| Synonyms | |

The apple is the pomaceous fruit of the apple tree, species Malus domestica in the rose family (Rosaceae). It is one of the most widely cultivated tree fruits, and the most widely known of the many members of genus Malus that are used by humans. Apples grow on small, deciduous trees. The tree originated in Central Asia, where its wild ancestor, Malus sieversii, is still found today. Apples have been grown for thousands of years in Asia and Europe, and were brought to North America by European colonists. Apples have been present in the mythology and religions of many cultures, including Norse, Greek and Christian traditions. In 2010, the fruit's genome was decoded, leading to new understandings of disease control and selective breeding in apple production.

There are more than 7,500 known cultivars of apples, resulting in a range of desired characteristics. Different cultivars are bred for various tastes and uses, including cooking, fresh eating and cider production. Domestic apples are generally propagated bygrafting, although wild apples grow readily from seed. Trees are prone to a number of fungal, bacterial and pest problems, which can be controlled by a number of organic and non-organic means.

About 69 million tonnes of apples were grown worldwide in 2010, and China produced almost half of this total. The United States is the second-leading producer, with more than 6% of world production. Turkey is third, followed by Italy, India and Poland. Apples are often eaten raw, but can also be found in many prepared foods (especially desserts) and drinks. Many beneficial health effects have been found from eating apples; however, two forms of allergies are seen to various proteins found in the fruit.

Contents[hide] |

Botanical information

The apple forms a tree that is small and deciduous, reaching 3 to 12 metres (9.8 to 39 ft) tall, with a broad, often densely twiggy crown.[3] The leaves are alternately arranged simple ovals 5 to 12 cm long and 3–6 centimetres (1.2–2.4 in) broad on a 2 to 5 centimetres (0.79 to 2.0 in) petiole with an acute tip, serrated margin and a slightly downy underside. Blossoms are produced in spring simultaneously with the budding of the leaves. The flowers are white with a pink tinge that gradually fades, five petaled, and 2.5 to 3.5 centimetres (0.98 to 1.4 in) in diameter. The fruit matures in autumn, and is typically 5 to 9 centimetres (2.0 to 3.5 in) in diameter. The skins of ripe apples range from red to yellow to green in colouration, and covered in a protective layer of epicuticular wax[4], while the flesh is pale yellowish-white. The center of the fruit contains five carpels arranged in a five-point star, each carpel containing one to three seeds, called pips.[3]

Wild ancestors

The original wild ancestor of Malus domestica was Malus sieversii, found growing wild in the mountains of Central Asia in southern Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Xinjiang, China.[3][5] Cultivation of the species, most likely beginning on the forested flanks of the Tian Shan mountains, progressed over a long period of time and permitted secondary introgression of genes from other species into the open-pollinated seeds. Significant exchange with Malus sylvestris, the crabapple, resulted in current populations of apples to be more related to crabapples than to the more morphologically similar progenitor Malus sieversii. In strains without recent admixture the contribution of the latter predominates.[6][7][8]

Genome

In 2010, an Italian-led consortium announced they had decoded the complete genome of the apple in collaboration with horticultural genomicists at Washington State University,[9] using the Golden delicious variety.[10] It had about 57,000 genes, the highest number of any plant genome studied to date[11] and more genes than the human genome (about 30,000).[12] This new understanding of the apple genome will help scientists in identifying genes and gene variants that contribute to resistance to disease and drought, and other desirable characteristics. Understanding the genes behind these characteristics will allow scientists to perform more knowledgeable selective breeding. Decoding the genome also provided proof that Malus sieversii was the wild ancestor of the domestic apple—an issue that had been long-debated in the scientific community.[13]

History

The center of diversity of the genus Malus is in eastern Turkey. The apple tree was perhaps the earliest tree to be cultivated,[14]and its fruits have been improved through selection over thousands of years. Alexander the Great is credited with finding dwarfed apples in Kazakhstan in Asia in 328 BCE;[3] those he brought back to Macedonia might have been the progenitors of dwarfing root stocks. Winter apples, picked in late autumn and stored just above freezing, have been an important food in Asia and Europe for millennia, as well as in Argentina and in the United States since the arrival of Europeans.[14] Apples were brought to North America by colonists in the 17th century,[3] and the first apple orchard on the North American continent was planted in Boston by ReverendWilliam Blaxton in 1625.[15] The only apples native to North America are crab apples, which were once called "common apples".[16]Apple varieties brought as seed from Europe were spread along Native American trade routes, as well as being cultivated on Colonial farms. An 1845 United States apples nursery catalogue sold 350 of the "best" varieties, showing the proliferation of new North American varieties by the early 19th century.[16] In the 20th century, irrigation projects in Washington state began and allowed the development of the multibillion dollar fruit industry, of which the apple is the leading product.[3]

Until the 20th century, farmers stored apples in frostproof cellars during the winter for their own use or for sale. Improved transportation of fresh apples by train and road replaced the necessity for storage.[17][18] In the 21st century, long-term storage again came into popularity, as "controlled atmosphere" facilities were used to keep apples fresh year-round. Controlled atmosphere facilities use high humidity and low oxygen and carbon dioxide levels to maintain fruit freshness.[19]

Cultural aspects

Germanic paganism

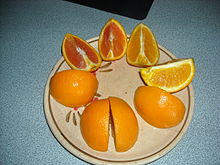

orange

Orange (fruit)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaThis article is about the fruit. For the colour, see Orange (colour). For other uses, see Orange (disambiguation)."Orange trees" redirects here. For the painting by Gustave Caillebotte, see Les orangers.

This article needs attention from an expert in botany. The specific problem is: Some information seems imprecise and some sources may be outdated. (November 2012)

Orange

Orange blossoms and oranges on tree Scientific classification Kingdom: Plantae (unranked): Angiosperms (unranked): Eudicots (unranked): Rosids Order: Sapindales Family: Rutaceae Genus: Citrus Species: C. × sinensis Binomial name Citrus × sinensis

(L.) Osbeck[1]

The orange (specifically, the sweet orange) is the fruit of the citrus species Citrus × ?sinensis in the familyRutaceae.[2] The fruit of the Citrus sinensis is called sweet orange to distinguish it from that of the Citrus aurantium, the bitter orange. The orange is a hybrid, possibly between pomelo (Citrus maxima) and mandarin (Citrus reticulata), cultivated since ancient times.[3]

Probably originated in Southeast Asia,[4] oranges were already cultivated in China as far back as 2500 BC. Between the late 15th century and the beginnings of the 16th century, Italian and Portuguese merchants brought orange trees in the Mediterranean area. The Spanish introduced the sweet orange to the American continent in the mid-1500s.

Orange trees are widely grown in tropical and subtropical climates for its sweet fruit, which can be eaten fresh or processed to obtain juice, and for its fragrant peel.[4] They have been the most cultivated tree fruit in the world since 1987,[5] and sweet oranges account for approximately 70% of the citrus production.[6] In 2010, 68.3 million tonnes of oranges were grown worldwide, particularly in Brazil and in the US states of California[7] and Florida.[8]

The origin of the term orange is presumably the Sanskrit word for "orange tree" (???????, n?ra?ga),[9] whose form has changed over time, after passing through numerous intermediate languages. The fruit is known as "Chinese apple" in several modern languages. Some examples are Dutch sinaasappel[10] (literally, "China's apple") and appelsien, orLow German Apfelsine. In English, however, Chinese apple usually refers to the pomegranate.[11]

| This article needs attention from an expert in botany. The specific problem is: Some information seems imprecise and some sources may be outdated. (November 2012) |

| Orange | |

|---|---|

| |

| Orange blossoms and oranges on tree | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Rosids |

| Order: | Sapindales |

| Family: | Rutaceae |

| Genus: | Citrus |

| Species: | C. × sinensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Citrus × sinensis (L.) Osbeck[1] | |

The orange (specifically, the sweet orange) is the fruit of the citrus species Citrus × ?sinensis in the familyRutaceae.[2] The fruit of the Citrus sinensis is called sweet orange to distinguish it from that of the Citrus aurantium, the bitter orange. The orange is a hybrid, possibly between pomelo (Citrus maxima) and mandarin (Citrus reticulata), cultivated since ancient times.[3]

Probably originated in Southeast Asia,[4] oranges were already cultivated in China as far back as 2500 BC. Between the late 15th century and the beginnings of the 16th century, Italian and Portuguese merchants brought orange trees in the Mediterranean area. The Spanish introduced the sweet orange to the American continent in the mid-1500s.

Orange trees are widely grown in tropical and subtropical climates for its sweet fruit, which can be eaten fresh or processed to obtain juice, and for its fragrant peel.[4] They have been the most cultivated tree fruit in the world since 1987,[5] and sweet oranges account for approximately 70% of the citrus production.[6] In 2010, 68.3 million tonnes of oranges were grown worldwide, particularly in Brazil and in the US states of California[7] and Florida.[8]

The origin of the term orange is presumably the Sanskrit word for "orange tree" (???????, n?ra?ga),[9] whose form has changed over time, after passing through numerous intermediate languages. The fruit is known as "Chinese apple" in several modern languages. Some examples are Dutch sinaasappel[10] (literally, "China's apple") and appelsien, orLow German Apfelsine. In English, however, Chinese apple usually refers to the pomegranate.[11]

Contents

Botanical information and terminology

All citrus trees belong to the single genus Citrus and remain almost entirely interfertile. This means that there is only one superspecies that includes grapefruits, lemons, limes, oranges and various other types and hybrids.[12] As the interfertility of oranges and other citrus has produced numerous hybrids, bud unions andcultivars, their taxonomy is fairly controversial, confusing or inconsistent.[3][6] The fruit of any citrus tree is considered a hesperidium (a kind of modified berry) because it has numerous seeds, is fleshy and soft, derives from a single ovary and is covered by a rind originated by a rugged thickening of the ovary wall.[13][14]

Different names have been given to the many varieties of the genus. Orange applies primarily to the sweet orange – Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck. The orange tree is an evergreen, flowering tree, with an average height of 9 to 10 metres (30 to 33 ft), although some very old specimens can reach 15 metres (49 ft).[15] Its ovalleaves, alternately arranged, are 4 to 10 centimetres (1.6 to 3.9 in) long and have crenulate margins.[16] Although the sweet orange presents different sizes and shapes varying from spherical to oblong, it generally has ten segments (carpels) inside, contains up to six seeds (or pips)[17] and a porous white tissue – called pith or, more properly,mesocarp or albedo –[18] lines its rind. When unripe, the fruit is green. The grainy irregular rind of the ripe fruit can range from bright orange to yellow-orange, but frequently retains green patches or, under warm climate conditions, remains entirely green. Like all other citrus fruits, the sweet orange is non-climacteric. The Citrus sinensis is subdivided into four classes with distinct characteristics: common oranges, blood or pigmented oranges, navel oranges and acidless oranges.[19][20][21]

Other citrus species also known as oranges are:

- the bitter orange (Citrus aurantium), also known as Seville orange, sour orange – especially when used as rootstock for a sweet orange tree –, bigarade orange and marmalade orange;

- the bergamot orange (Citrus bergamia Risso). It is grown mainly in Italy for its peel, which is used to flavour Earl Grey tea;

- the trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata), sometimes included in the genus (classified as Citrus trifoliata). It often serves as arootstock for sweet orange trees, especially as a hybrid with other Citrus cultivars. The trifoliate orange is a thorny shrub or small tree grown mostly as an ornamental plant or to set up hedges. It bears a downy fruit similar to a small citrus, used to make marmalade. It is native to northern China and Korea, and is also known as "Chinese bitter orange" or "hardy orange" because it can withstand subfreezing temperatures;[22] and

- the mandarin orange (Citrus reticulata). It has an enormous number of cultivars, most notably the satsuma (Citrus unshiu), thetangerine (Citrus tangerina) and the clementine (Citrus clementina). In some cultivars, the mandarin is very similar to the sweet orange, making it difficult to distinguish the two. The mandarin, though, is generally smaller and oblate, easier to peel and less acid.[23]

Orange trees are generally grafted. The bottom of the tree, including the roots and trunk, is called rootstock, while the fruit-bearing top has two different names: budwood (when referring to the process of grafting) and scion (when mentioning the variety of orange).[24]

All citrus trees belong to the single genus Citrus and remain almost entirely interfertile. This means that there is only one superspecies that includes grapefruits, lemons, limes, oranges and various other types and hybrids.[12] As the interfertility of oranges and other citrus has produced numerous hybrids, bud unions andcultivars, their taxonomy is fairly controversial, confusing or inconsistent.[3][6] The fruit of any citrus tree is considered a hesperidium (a kind of modified berry) because it has numerous seeds, is fleshy and soft, derives from a single ovary and is covered by a rind originated by a rugged thickening of the ovary wall.[13][14]

Different names have been given to the many varieties of the genus. Orange applies primarily to the sweet orange – Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck. The orange tree is an evergreen, flowering tree, with an average height of 9 to 10 metres (30 to 33 ft), although some very old specimens can reach 15 metres (49 ft).[15] Its ovalleaves, alternately arranged, are 4 to 10 centimetres (1.6 to 3.9 in) long and have crenulate margins.[16] Although the sweet orange presents different sizes and shapes varying from spherical to oblong, it generally has ten segments (carpels) inside, contains up to six seeds (or pips)[17] and a porous white tissue – called pith or, more properly,mesocarp or albedo –[18] lines its rind. When unripe, the fruit is green. The grainy irregular rind of the ripe fruit can range from bright orange to yellow-orange, but frequently retains green patches or, under warm climate conditions, remains entirely green. Like all other citrus fruits, the sweet orange is non-climacteric. The Citrus sinensis is subdivided into four classes with distinct characteristics: common oranges, blood or pigmented oranges, navel oranges and acidless oranges.[19][20][21]

Other citrus species also known as oranges are:

- the bitter orange (Citrus aurantium), also known as Seville orange, sour orange – especially when used as rootstock for a sweet orange tree –, bigarade orange and marmalade orange;

- the bergamot orange (Citrus bergamia Risso). It is grown mainly in Italy for its peel, which is used to flavour Earl Grey tea;

- the trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata), sometimes included in the genus (classified as Citrus trifoliata). It often serves as arootstock for sweet orange trees, especially as a hybrid with other Citrus cultivars. The trifoliate orange is a thorny shrub or small tree grown mostly as an ornamental plant or to set up hedges. It bears a downy fruit similar to a small citrus, used to make marmalade. It is native to northern China and Korea, and is also known as "Chinese bitter orange" or "hardy orange" because it can withstand subfreezing temperatures;[22] and

- the mandarin orange (Citrus reticulata). It has an enormous number of cultivars, most notably the satsuma (Citrus unshiu), thetangerine (Citrus tangerina) and the clementine (Citrus clementina). In some cultivars, the mandarin is very similar to the sweet orange, making it difficult to distinguish the two. The mandarin, though, is generally smaller and oblate, easier to peel and less acid.[23]

Orange trees are generally grafted. The bottom of the tree, including the roots and trunk, is called rootstock, while the fruit-bearing top has two different names: budwood (when referring to the process of grafting) and scion (when mentioning the variety of orange).[24]

Varieties

Common oranges

Valencia

Main article: Valencia orangeThe Valencia orange is a late-season fruit, and therefore a popular variety when navel oranges are out of season. This is why an anthropomorphic orange was chosen as themascot for the 1982 FIFA World Cup, held in Spain. The mascot was named Naranjito ("little orange") and wore the colours of the Spanish national football team kit.

The Valencia orange is a late-season fruit, and therefore a popular variety when navel oranges are out of season. This is why an anthropomorphic orange was chosen as themascot for the 1982 FIFA World Cup, held in Spain. The mascot was named Naranjito ("little orange") and wore the colours of the Spanish national football team kit.

Hart's Tardiff Valencia

Thomas Rivers, an English nurseryman, imported this variety from the Azores Islands and catalogued it in 1865 under the name Excelsior. Around 1870, he provided trees to S. B. Parsons, a Long Island nurseryman, who in turn sold them to E. H. Hart of Federal Point, Florida.[25]

Thomas Rivers, an English nurseryman, imported this variety from the Azores Islands and catalogued it in 1865 under the name Excelsior. Around 1870, he provided trees to S. B. Parsons, a Long Island nurseryman, who in turn sold them to E. H. Hart of Federal Point, Florida.[25]

Hamlin

This cultivar was discovered by A.G. Hamlin near Glenwood, Florida, in 1879. The fruit is small, smooth, not highly coloured, seedless and juicy, with a pale yellow coloured juice, especially in fruits that come from lemon rootstock. The tree is high-yielding and cold-tolerant and produces good quality fruit, which is harvested from October to December. It thrives in humid subtropical climates. In cooler, more arid areas, the trees produce edible fruit, but too small for commercial use.[15]

Trees from groves in hammocks or areas covered with pine forest are budded on sour orange trees, a method that gives a high solids content. On sand, they are grafted on rough lemon rootstock.[5] The Hamlin orange is one of the most popular juice oranges in Florida and replaces the Parson Brown variety as the principal early-season juice orange. This cultivar is now[needs update] the leading early orange in Florida and, possibly, in the rest of the world.[15]

This cultivar was discovered by A.G. Hamlin near Glenwood, Florida, in 1879. The fruit is small, smooth, not highly coloured, seedless and juicy, with a pale yellow coloured juice, especially in fruits that come from lemon rootstock. The tree is high-yielding and cold-tolerant and produces good quality fruit, which is harvested from October to December. It thrives in humid subtropical climates. In cooler, more arid areas, the trees produce edible fruit, but too small for commercial use.[15]

Trees from groves in hammocks or areas covered with pine forest are budded on sour orange trees, a method that gives a high solids content. On sand, they are grafted on rough lemon rootstock.[5] The Hamlin orange is one of the most popular juice oranges in Florida and replaces the Parson Brown variety as the principal early-season juice orange. This cultivar is now[needs update] the leading early orange in Florida and, possibly, in the rest of the world.[15]

Other varieties of common oranges

- Belladonna: grown in Italy.

- Berna: grown mainly in Spain.

- Biondo Commune ("ordinary blond"): widely grown in the Mediterranean basin, especially in North Africa, Egypt, Greece (where it is called "koines"), Italy (where it is also known as "Liscio") and Spain. It is also called "Beledi" and "Nostrale".[19] In Italy, this variety ripens in December, earlier than the competing Tarocco.[26]

- Biondo Riccio: grown in Italy.

- Cadanera: a seedless orange of excellent flavour grown in Algeria, Morocco and Spain. It begins to ripen in November and is known by a wide variety of trade names, such as Cadena Fina, Cadena sin Jueso, Precoce de Valence ("early from Valencia"), Precoce des Canaries and Valence san Pepins ("seedless Valencia").[19] It was first grown in Spain in 1870.[27]

- Calabrese or Calabrese Ovale: grown in Italy.

- Carvalhal: grown in Portugal.

- Castellana: grown in Spain.

- Clanor: grown in South Africa.

- Dom João: grown in Portugal.

- Fukuhara: grown in Japan.

- Gardner: grown in Florida. This mid-season orange ripens around the beginning of February, around the same time as the Midsweet variety. Gardner is about as hardy as Sunstar and Midsweet.[28]

- Homosassa: grown in Florida.

- Jaffa orange: grown in the Middle East, also known as "Shamouti".

- Jincheng: the most popular orange in China.

- Joppa: grown in South Africa and Texas.

- Khettmali: grown in Israel and Lebanon.

- Kona: a type of Valencia orange introduced in Hawaii in 1792 by Captain George Vancouver. For many decades in the 19th century, these oranges were the leading export from the Kona district on the Big Island of Hawaii. In Kailua-Kona, some of the original stock still bears fruit.

- Lue Gim Gong: grown in Florida. It is an early scion developed by Lue Gim Gong, a Chinese immigrant known as the "Citrus Genius". In 1888, Lue cross-pollinated two orange varieties – the Hart's late Valencia and the Mediterranean Sweet – and obtained a fruit both sweet and frost-tolerant. This variety was propagated at the Glen St. Mary Nursery, which in 1911 received the Silver Wilder Medal by the American Pomological Society.[5][29] Originally considered a hybrid, the Lue Gim Gong orange was later found to be a nucellar seedling of the Valencia type,[30] which is properly called Lue Gim Gong. As from 2006, the Lue Gim Gong variety is grown in Florida, although sold under the general name Valencia.

- Macetera: grown in Spain, it is known for its unique flavour.

- Malta: grown in Pakistan.

- Maltaise Blonde: grown in north Africa.

- Maltaise Ovale: grown in South Africa and in California under the names of Garey's or California Mediterranean Sweet.

- Marrs: grown in Texas, California and Iran, it is relatively low in acid.

- Midsweet: grown in Florida, it is a newer scion similar to the Hamlin and Pineapple varieties. It is hardier than Pineapple and ripens later. The fruit production and quality are similar to those of the Hamlin, but the juice has a deeper colour.[28]

- Moro Tarocco: grown in Italy. It is oval, resembles a tangelo and has a distinctive caramel-coloured endocarp. This colour is the result of a pigment called anthocarpium, not usually found in citruses, but common in red fruits and flowers. The original mutation occurred in Sicily in the 17th century.

- Mosambi: grown in India and Pakistan, it is so low in acid and insipid that it might be classified as acidless.

- Narinja: grown in Andhra, South India.

- Parson Brown: grown in Florida, Mexico and Turkey. Once a widely grown Florida juice orange, its popularity has declined since new varieties with more juice, better yield and higher acid and sugar content have been developed. It originated as a chance seedling in Florida in 1865. Its fruits are round, medium large, have a thick, pebbly peel and contain 10 to 30 seeds. It is still grown because it is the earliest maturing fruit in the United States: usually matures in early September in the Valley district of Texas,[21] and from early October to January in Florida.[28] Its peel and juice colour are poor, as is the quality of its juice.[21]

- Pera: grown in Brazil. It is very popular in the Brazilian citrus industry and yielded 7.5 million tonnes in 2005.

- Pera Coroa: grown in Brazil.

- Pera Natal: grown in Brazil.

- Pera Rio: grown in Brazil.

- Pineapple: grown in North and South America and India.

- Premier: grown in South Africa.

- Rhode Red: is a mutation of the Valencia orange, but the colour of its flesh is more intense. It has more juice, and less acidity and vitamin C. It was discovered by Paul Rhode in 1955 in a grove near Sebring, Florida.

- Roble: it was first shipped from Spain in 1851 by Joseph Roble to his homestead in what is now Roble's Park in Tampa, Florida. It is known for its high sugar content.

- Queen: grown in South Africa.

- Salustiana: grown in North Africa.

- Sathgudi: grown in Tamil Nadu, South India.

- Seleta, Selecta: grown in Australia and Brazil. It is high in acid.

- Shamouti Masry: grown in Egypt. It is a richer variety of Shamouti.

- Sunstar: grown in Florida. This newer cultivar ripens in mid-season (December to March) and it is more resistant to cold and fruit-drop than the competing Pineapple variety. The colour of its juice is darker than that of the competing Hamlin.[28]

- Tomango: grown in South Africa.

- Verna: grown in Algeria, Mexico, Morocco and Spain.

- Vicieda: grown in Algeria, Morocco and Spain.

- Westin: grown in Brazil.

- Belladonna: grown in Italy.

- Berna: grown mainly in Spain.

- Biondo Commune ("ordinary blond"): widely grown in the Mediterranean basin, especially in North Africa, Egypt, Greece (where it is called "koines"), Italy (where it is also known as "Liscio") and Spain. It is also called "Beledi" and "Nostrale".[19] In Italy, this variety ripens in December, earlier than the competing Tarocco.[26]

- Biondo Riccio: grown in Italy.

- Cadanera: a seedless orange of excellent flavour grown in Algeria, Morocco and Spain. It begins to ripen in November and is known by a wide variety of trade names, such as Cadena Fina, Cadena sin Jueso, Precoce de Valence ("early from Valencia"), Precoce des Canaries and Valence san Pepins ("seedless Valencia").[19] It was first grown in Spain in 1870.[27]

- Calabrese or Calabrese Ovale: grown in Italy.

- Carvalhal: grown in Portugal.

- Castellana: grown in Spain.

- Clanor: grown in South Africa.

- Dom João: grown in Portugal.

- Fukuhara: grown in Japan.

- Gardner: grown in Florida. This mid-season orange ripens around the beginning of February, around the same time as the Midsweet variety. Gardner is about as hardy as Sunstar and Midsweet.[28]

- Homosassa: grown in Florida.

- Jaffa orange: grown in the Middle East, also known as "Shamouti".

- Jincheng: the most popular orange in China.

- Joppa: grown in South Africa and Texas.

- Khettmali: grown in Israel and Lebanon.

- Kona: a type of Valencia orange introduced in Hawaii in 1792 by Captain George Vancouver. For many decades in the 19th century, these oranges were the leading export from the Kona district on the Big Island of Hawaii. In Kailua-Kona, some of the original stock still bears fruit.

- Lue Gim Gong: grown in Florida. It is an early scion developed by Lue Gim Gong, a Chinese immigrant known as the "Citrus Genius". In 1888, Lue cross-pollinated two orange varieties – the Hart's late Valencia and the Mediterranean Sweet – and obtained a fruit both sweet and frost-tolerant. This variety was propagated at the Glen St. Mary Nursery, which in 1911 received the Silver Wilder Medal by the American Pomological Society.[5][29] Originally considered a hybrid, the Lue Gim Gong orange was later found to be a nucellar seedling of the Valencia type,[30] which is properly called Lue Gim Gong. As from 2006, the Lue Gim Gong variety is grown in Florida, although sold under the general name Valencia.

- Macetera: grown in Spain, it is known for its unique flavour.

- Malta: grown in Pakistan.

- Maltaise Blonde: grown in north Africa.

- Maltaise Ovale: grown in South Africa and in California under the names of Garey's or California Mediterranean Sweet.

- Marrs: grown in Texas, California and Iran, it is relatively low in acid.

- Midsweet: grown in Florida, it is a newer scion similar to the Hamlin and Pineapple varieties. It is hardier than Pineapple and ripens later. The fruit production and quality are similar to those of the Hamlin, but the juice has a deeper colour.[28]

- Moro Tarocco: grown in Italy. It is oval, resembles a tangelo and has a distinctive caramel-coloured endocarp. This colour is the result of a pigment called anthocarpium, not usually found in citruses, but common in red fruits and flowers. The original mutation occurred in Sicily in the 17th century.

- Mosambi: grown in India and Pakistan, it is so low in acid and insipid that it might be classified as acidless.

- Narinja: grown in Andhra, South India.

- Parson Brown: grown in Florida, Mexico and Turkey. Once a widely grown Florida juice orange, its popularity has declined since new varieties with more juice, better yield and higher acid and sugar content have been developed. It originated as a chance seedling in Florida in 1865. Its fruits are round, medium large, have a thick, pebbly peel and contain 10 to 30 seeds. It is still grown because it is the earliest maturing fruit in the United States: usually matures in early September in the Valley district of Texas,[21] and from early October to January in Florida.[28] Its peel and juice colour are poor, as is the quality of its juice.[21]

- Pera: grown in Brazil. It is very popular in the Brazilian citrus industry and yielded 7.5 million tonnes in 2005.

- Pera Coroa: grown in Brazil.

- Pera Natal: grown in Brazil.

- Pera Rio: grown in Brazil.

- Pineapple: grown in North and South America and India.

- Premier: grown in South Africa.

- Rhode Red: is a mutation of the Valencia orange, but the colour of its flesh is more intense. It has more juice, and less acidity and vitamin C. It was discovered by Paul Rhode in 1955 in a grove near Sebring, Florida.

- Roble: it was first shipped from Spain in 1851 by Joseph Roble to his homestead in what is now Roble's Park in Tampa, Florida. It is known for its high sugar content.

- Queen: grown in South Africa.

- Salustiana: grown in North Africa.

- Sathgudi: grown in Tamil Nadu, South India.

- Seleta, Selecta: grown in Australia and Brazil. It is high in acid.

- Shamouti Masry: grown in Egypt. It is a richer variety of Shamouti.

- Sunstar: grown in Florida. This newer cultivar ripens in mid-season (December to March) and it is more resistant to cold and fruit-drop than the competing Pineapple variety. The colour of its juice is darker than that of the competing Hamlin.[28]

- Tomango: grown in South Africa.

- Verna: grown in Algeria, Mexico, Morocco and Spain.

- Vicieda: grown in Algeria, Morocco and Spain.

- Westin: grown in Brazil.

Navel oranges are characterized by the growth of a second fruit at the apex, which protrudes slightly and resembles a human navel. They are primarily grown for human consumption for various reasons: their thicker skin make them easier to peel, they are less juicy and their bitterness – a result of the high concentrations of limonin and otherlimonoids – renders them less suitable for juice.[19] Their widespread distribution and long growing season have made navel oranges very popular. In the United States, they are available from November to April, with peak supplies in January, February and March.[31]

According to a 1917 study by Palemon Dorsett, Archibald Dixon Shamel and Wilson Popenoe of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), a single mutation in a Selecta orange tree planted on the grounds of a monastery near Bahia, Brazil, probably yielded the first navel orange between 1810 and 1820.[32] Nevertheless, a researcher at the University of California, Riverside, has suggested that the parent variety was more likely the Portuguese navel orange (Umbigo), described by Antoine Risso and Pierre Antoine Poiteau in their book Histoire naturelle des orangers ("Natural History of Orange Trees", 1818–1822).[32] The mutation caused the orange to develop a second fruit at its base, opposite the stem, as a conjoined twin in a set of smaller segments embedded within the peel of the primary orange.[33] Navel oranges were introduced in Australia in 1824 and in Florida in 1835. In 1870, twelve cuttings of the original tree were transplanted to Riverside, California, where the fruit became known as "Washington".[34] This cultivar was very successful, and rapidly spread to other countries.[32] Because the mutation left the fruit seedless and, therefore, sterile, the only method to cultivate navel oranges was to graft cuttings on to other varieties of citrus tree. The California Citrus State Historic Park and the Orcutt Ranch Horticulture Center preserve the history of navel oranges in Riverside.

Today, navel oranges continue to be propagated through cutting and grafting. This does not allow for the usual selective breedingmethodologies, and so all navel oranges can be considered fruits from that single nearly two-hundred-year-old tree: they have exactly the same genetic make-up as the original tree and are, therefore, clones. This case is similar to that of the common yellow seedless banana, the Cavendish. On rare occasions, however, further mutations can lead to new varieties.[32]

Navel oranges are characterized by the growth of a second fruit at the apex, which protrudes slightly and resembles a human navel. They are primarily grown for human consumption for various reasons: their thicker skin make them easier to peel, they are less juicy and their bitterness – a result of the high concentrations of limonin and otherlimonoids – renders them less suitable for juice.[19] Their widespread distribution and long growing season have made navel oranges very popular. In the United States, they are available from November to April, with peak supplies in January, February and March.[31]

According to a 1917 study by Palemon Dorsett, Archibald Dixon Shamel and Wilson Popenoe of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), a single mutation in a Selecta orange tree planted on the grounds of a monastery near Bahia, Brazil, probably yielded the first navel orange between 1810 and 1820.[32] Nevertheless, a researcher at the University of California, Riverside, has suggested that the parent variety was more likely the Portuguese navel orange (Umbigo), described by Antoine Risso and Pierre Antoine Poiteau in their book Histoire naturelle des orangers ("Natural History of Orange Trees", 1818–1822).[32] The mutation caused the orange to develop a second fruit at its base, opposite the stem, as a conjoined twin in a set of smaller segments embedded within the peel of the primary orange.[33] Navel oranges were introduced in Australia in 1824 and in Florida in 1835. In 1870, twelve cuttings of the original tree were transplanted to Riverside, California, where the fruit became known as "Washington".[34] This cultivar was very successful, and rapidly spread to other countries.[32] Because the mutation left the fruit seedless and, therefore, sterile, the only method to cultivate navel oranges was to graft cuttings on to other varieties of citrus tree. The California Citrus State Historic Park and the Orcutt Ranch Horticulture Center preserve the history of navel oranges in Riverside.

Today, navel oranges continue to be propagated through cutting and grafting. This does not allow for the usual selective breedingmethodologies, and so all navel oranges can be considered fruits from that single nearly two-hundred-year-old tree: they have exactly the same genetic make-up as the original tree and are, therefore, clones. This case is similar to that of the common yellow seedless banana, the Cavendish. On rare occasions, however, further mutations can lead to new varieties.[32]

Cara cara oranges (also called "red navel") are a type of navel orange grown mainly in Venezuela, South Africa and in California's San Joaquin Valley. They are sweet and comparatively low in acid,[35] with a bright orange rind similar to that of other navels, but their flesh is distinctively pinkish red. It is believed that they have originated as a cross between the Washington navel and the Brazilian Bahia navel[36] and were discovered in the Hacienda Cara Cara in Valencia, Venezuela, in 1976.[37]

South African cara caras are ready for market in early August, while Venezuelan fruits arrive in October and Californian fruits in late November.[35][36]

Cara cara oranges (also called "red navel") are a type of navel orange grown mainly in Venezuela, South Africa and in California's San Joaquin Valley. They are sweet and comparatively low in acid,[35] with a bright orange rind similar to that of other navels, but their flesh is distinctively pinkish red. It is believed that they have originated as a cross between the Washington navel and the Brazilian Bahia navel[36] and were discovered in the Hacienda Cara Cara in Valencia, Venezuela, in 1976.[37]

South African cara caras are ready for market in early August, while Venezuelan fruits arrive in October and Californian fruits in late November.[35][36]

- Bahianinha or Bahia

- Dream Navel

- Late Navel

- Washington or California Navel

- Bahianinha or Bahia

- Dream Navel

- Late Navel

- Washington or California Navel

Blood oranges

blue berry

Blueberry

| Blueberry | |

|---|---|

| |

| Vaccinium corymbosum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Asterids |

| Order: | Ericales |

| Family: | Ericaceae |

| Genus: | Vaccinium |

| Section: | Cyanococcus Rydb. |

| Species | |

See text | |

Blueberries are perennial flowering plants with indigo-colored berries in the section Cyanococcus within the genus Vaccinium (a genus that also includes cranberries and bilberries). Species in the section Cyanococcus are the most common[1] fruits sold as "blueberries" and are native to North America (commercially cultivated highbush blueberries were not introduced into Europe until the 1930s).[2]

They are usually erect, but sometimes prostrate shrubs varying in size from 10 centimeters (3.9 in) to 4 meters (13 ft) tall. In commercial blueberry production, smaller species are known as "lowbush blueberries" (synonymous with "wild"), and the larger species are known as "highbush blueberries".

The leaves can be either deciduous or evergreen, ovate to lanceolate, and 1–8 cm (0.39–3.1 in) long and 0.5–3.5 cm (0.20–1.4 in) broad. The flowers are bell-shaped, white, pale pink or red, sometimes tinged greenish. The fruit is a berry 5–16 millimeters (0.20–0.63 in) in diameter with a flared crown at the end; they are pale greenish at first, then reddish-purple, and finally dark blue when ripe. They are covered in a protective coating of powdery epicuticular wax, colloquially knows as the "bloom".[3] They have a sweet taste when mature, with variable acidity. Blueberry bushes typically bear fruit in the middle of the growing season: fruiting times are affected by local conditions such as altitude and latitude, so the height of the crop can vary from May to August depending upon these conditions.

Contents[hide] |

Origins[edit]

The genus Vaccinium has a mostly circumpolar distribution with species in America, Europe, Asia, and Africa.

Many commercially sold species with English common names including "blueberry" are currently classified in section Cyanococcus of the genus Vaccinium and come predominantly from North America. Many North American native species of blueberries are now also commercially grown in the Southern Hemisphere in Australia, New Zealand and South American countries.

Several other wild shrubs of the genus Vaccinium also produce commonly eaten blue berries, such as the predominantly European Vaccinium myrtillus and other bilberries, that in many languages have a name that translates "blueberry" in English. See the Identification section for more information.

Species[edit]

Note: habitat and range summaries are from the Flora of New Brunswick, published in 1986 by Harold R. Hinds and Plants of the Pacific Northwest coast, published in 1994 by Pojar and MacKinnon

- Vaccinium alaskaense (Alaskan blueberry): one of the dominant shrubs in Alaskan and British Columbian coastal forests

- Vaccinium angustifolium (lowbush blueberry): acidic barrens, bogs and clearings, Manitoba to Labrador, south to Nova Scotia and in the USA, to Iowa and Virginia

- Vaccinium boreale (northern blueberry): peaty barrens, Quebec and Labrador (rare in New Brunswick), south to New York and Massachusetts

- Vaccinium caesariense (New Jersey blueberry)

- Vaccinium corymbosum (northern highbush blueberry)

- Vaccinium constablaei (hillside blueberry)

- Vaccinium darrowii (evergreen blueberry)

- Vaccinium elliottii (Elliott blueberry)

- Vaccinium formosum (southern blueberry)

- Vaccinium fuscatum (black highbush blueberry; syn. V. atrococcum)

- Vaccinium hirsutum (hairy-fruited blueberry)

- Vaccinium myrsinites (shiny blueberry)

- Vaccinium myrtilloides (sour top, velvet leaf, or Canadian blueberry)

- Vaccinium operium (cyan-fruited blueberry)

- Vaccinium pallidum (dryland blueberry)

- Vaccinium simulatum (upland highbush blueberry)

- Vaccinium tenellum (southern blueberry)

- Vaccinium virgatum (rabbiteye blueberry; syn. V. ashei)

Some other blue-fruited species of Vaccinium:

- Vaccinium koreanum

- Vaccinium myrtillus (bilberry or European blueberry)

- Vaccinium uliginosum

Identification[edit]

Commercially offered blueberries are usually from species that naturally occur only in eastern and north-central North America. Other sections in the genus, native to other parts of the world, including the Pacific Northwest and southern United States,[4] South America, Europe, and Asia, include other wild shrubs producing similar-looking edible berries, such as huckleberries andwhortleberries (North America) and bilberries (Europe). These species are sometimes called "blueberries" and sold as blueberry jam or other products.

The names of blueberries in languages other than English often translate as "blueberry", e.g., Scots blaeberry and Norwegianblåbær. Blaeberry, blåbær and French myrtilles usually refer to the European native bilberry (V. myrtillus), while bleuets refers to the North American blueberry.

Cyanococcus blueberries can be distinguished from the nearly identical-looking bilberries by their flesh color when cut in half. Ripe blueberries have light green flesh, while bilberries, whortleberries and huckleberries are red or purple throughout.

Cultivation[edit]

Blueberries may be cultivated, or they may be picked from semiwild or wild bushes. In North America, the most common cultivated species is V. corymbosum, the northern highbush blueberry. Hybrids of this with other Vaccinium species adapted to southern U.S. climates are known collectively as southern highbush blueberries.[citation needed]

So-called "wild" (lowbush) blueberries, smaller than cultivated highbush ones, are prized for their intense color. The lowbush blueberry, V. angustifolium, is found from the Atlantic provinces westward to Quebec and southward to Michigan and West Virginia. In some areas, it produces natural "blueberry barrens", where it is the dominant species covering large areas. Several First Nationscommunities in Ontario are involved in harvesting wild blueberries. Lowbush species are fire-tolerant and blueberry production often increases following a forest fire, as the plants regenerate rapidly and benefit from removal of competing vegetation.[citation needed]

"Wild" has been adopted as a marketing term for harvests of managed native stands of lowbush blueberries. The bushes are not planted or genetically manipulated, but they are pruned or burned over every two years, and pests are "managed".[5]

Numerous highbush cultivars of blueberries are available, with diversity among them, each having a unique flavor. The most important blueberry breeding program has been the USDA-ARS breeding program based at Beltsville, Maryland, and Chatsworth, New Jersey. This program began when Frederick Coville of the USDA-ARS collaborated with Elizabeth Coleman White of New Jersey.[6] In the early part of the 20th century, White offered pineland residents cash for wild blueberry plants with unusually large fruit.[7] 'Rubel', one such wild blueberry cultivar, is the origin of many of the current hybrid cultivars.[citation needed]

The rabbiteye blueberry (Vaccinium virgatum syn. V. ashei) is a southern type of blueberry produced from the Carolinas to the Gulf Coast states. Other important species in North America include V. pallidum, the hillside or dryland blueberry. It is native to the eastern U.S., and common in the Appalachians and the Piedmont of the Southeast. Sparkleberry, V. arboreum, is a common wild species on sandy soils in the Southeast. Its fruits are important to wildlife, and the flowers are important to beekeepers.[citation needed]

Growing areas[edit]

Significant production of highbush blueberries occurs in British Columbia, Maryland, Western Oregon, Michigan, New Jersey, North Carolina, and Washington. The production of southern highbush varieties in California is rapidly increasing, as varieties originating from University of Florida, Connecticut, New Hampshire, North Carolina State University and Maine have been introduced. Southern highbush berries are now also cultivated in the Mediterranean regions of Europe, Southern Hemisphere countries and China.

United States[edit]

Maine produces 25% of all lowbush blueberries in North America with 24,291 hectares (60,020 acres) (FAO figures)[full citation needed] under cultivation.[citation needed] Wild blueberry is the official fruit of Maine.

Michigan is the leader in highbush production.[8] In 1998, Michigan farms produced 220,000 tonnes (490,000,000 lb) of blueberries, accounting for 32% of those eaten in the United States.[9]

Commercial acreages of highbush blueberries are cultivated in the states of New Jersey, Florida, Georgia and North Carolina.[10][11]

Canada[edit]

Canadian exports of blueberries in 2007 were C$323 million, the largest fruit crop produced nationally, occupying more than half of all Canadian fruit acreage.[12]

British Columbia is the largest Canadian producer of highbush blueberries, yielding 40 million kilograms in 2009, the world's largest production by region.[13][14]

Atlantic Canada contributes approximately half of the total North American wild/lowbush annual production of 68,000 t (150,000,000 lb).[15]

Nova Scotia, the biggest producer of wild blueberries in Canada, recognizes the blueberry as its official provincial berry.[16] The town of Oxford is known as the Wild Blueberry Capital of Canada. New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island are other Atlantic provinces with major wild blueberry farming.[17]

Quebec is a major producer of wild blueberries, especially in the regions of Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean (where a popular name for inhabitants of the regions is bleuets, or "blueberries") and Côte-Nord, which together provide 40% of Quebec's total provincial production.

Europe[edit]

Highbush blueberries were first introduced to Germany, Sweden and the Netherlands in the 1930s, and have since been spread to Romania, Poland, Italy, Hungary and other countries of Europe.[2]

Asia[edit]

The northeastern part of Turkey is one of the main sources of Caucasian whortleberry (V. arctostaphylos), bilberry (V. myrtillus) and bog blueberry, bog whortleberry or bog bilberry (V. uliginosum). This region from Artvin to K?rklareli, as well as parts of Bursa (including Rize, Trabzon, Ordu, Giresun, Samsun, Sinop, Kastamonu, Zonguldak, ?stanbul, ?zmit and Adapazari) have rainy, humid growing periods and naturally acidic soils suitable for blueberries (Çelik, 2005, 2006 and 2007).[full citation needed]

Native Vaccinium species and open-pollinated types have been grown for over a hundred years around the Black Sea region of Turkey. These native blueberries are eaten locally as jelly or dried or fresh fruit (Çelik, 2005).[full citation needed] Highbush blueberry cultivation started around the year 2000. The first commercial blueberry orchard was established by Osman Nuri Yildiz and supervised by Dr. Huseyin Celik, the founder of Turkish blueberry cultivation.[citation needed]

Southern Hemisphere[edit]

In the Southern Hemisphere, Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, South Africa, New Zealand, and Australia now export blueberries.

Blueberries were first introduced to Australia in the 1950s, but the effort was unsuccessful. In the early 1970s, David Jones from the Victorian Department of Agriculture imported seed from the U.S. and a selection trial was started. This work was continued by Ridley Bell, who imported more American varieties. In the mid-1970s, the Australian Blueberry Growers' Association was formed.[18][19]

By the early 1980s, the blueberry industry was started in New Zealand and is still growing.

South Africa exports blueberries to Europe.

Commercial blueberry production in Argentina was 400 hectares (990 acres) in 2001 and 1,600 hectares (4,000 acres) in 2004. Production in Argentina is increasing.[20] "Argentine blueberry production has thrived in four different regions: the province[s] of Entre Rios in northeastern Argentina, [...] Tucuman, Buenos Aires [...], and the southern Patagonian valleys", according to the report.[21]

Chile is the biggest producer in South America and the largest exporter to the Northern Hemisphere, with an estimated area of 12.400 hectares (30.64 acres) in 2012 (ODEPA/CIREN). Introduction of the first plants started in the early 1980s, and production started in the late 80s in the southern part of the country. Today, production ranges from Copiapó in the north to Puerto Montt in the south, which allows the country to offer blueberries from October through late March. The main production area today is the Biobío Region. Production has evolved rapidly in the last decade, becoming the fourth most important fruit exported in value terms. Blueberries are exported mainly to North America (80%), followed by Europe (18%).[22] Most of the production comes from the highbush type, but several rabbiteye blueberries are grown in the country, as well.[23]

In Peru, there are several private initiatives for the development of the crop. Also, the government through its agency Sierra Exportadora, has launched the program "Peru Berries" to take advantage of the existence of the ideal soil and climate required by the blueberry.

Harvesting[edit]

Harvest Seasons[edit]

The blueberry harvest in North America varies. It can start as early as May and usually ends in late summer. The principal areas of production in the Southern Hemisphere (Australia, Chile, New Zealand and Argentina) have long periods of harvest. In Australia, for example, due to the geographic spread of blueberry farms and the development of new cultivation techniques, the industry is able to provide fresh blueberries for 10 months of the year – from July through to April.[18] Similar to other fruits and vegetables, climate-controlled storage allows growers to preserve picked blueberries. Harvest in the UK is from June to August.

Harvest Methods[edit]

For many years, blueberries were hand picked. In modern times, traditional hand picking is still quite common especially for the more delicate varieties. More commonly, farmers will use harvesters that will shake the fruit off the bush. The fruit is then brought to a cleaning/packaging facility where it is cleaned, packaged, then sold.

Uses[edit]

Blueberries are sold fresh or processed as individually quick frozen (IQF) fruit, purée, juice, or dried or infused berries, which in turn may be used in a variety of consumer goods, such as jellies, jams, blueberry pies, muffins, snack foods and cereals.

Blueberry jam is made from blueberries, sugar, water, and fruit pectin. Blueberry wine is made from the flesh and skin of the berry, which is fermented and then matured; usually the lowbush variety is used.[24]

Nutrients, phytochemicals and research[edit]

stawberry

Strawberry

| Garden strawberry Fragaria × ananassa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Garden strawberries grown hydroponically | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Rosaceae |

| Subfamily: | Rosoideae |

| Genus: | Fragaria |

| Species: | F. × ananassa |

| Binomial name | |

| Fragaria × ananassa Duchesne | |

Fragaria × ananassa, commonly known as strawberry (/?str??b?ri/ or ![]() i/?str???b?ri/) or garden strawberry, is a hybrid speciesthat is cultivated worldwide for its fruit. The fruit (which is not a botanical berry, but an aggregate accessory fruit) is widely appreciated for its characteristic aroma, bright red color, juicy texture, and sweetness. It is consumed in large quantities, either fresh or in prepared foods such as preserves, fruit juice, pies, ice creams, milkshakes, and chocolates. Artificial strawberry aroma is also widely used in many industrialized food products.

i/?str???b?ri/) or garden strawberry, is a hybrid speciesthat is cultivated worldwide for its fruit. The fruit (which is not a botanical berry, but an aggregate accessory fruit) is widely appreciated for its characteristic aroma, bright red color, juicy texture, and sweetness. It is consumed in large quantities, either fresh or in prepared foods such as preserves, fruit juice, pies, ice creams, milkshakes, and chocolates. Artificial strawberry aroma is also widely used in many industrialized food products.

The garden strawberry was first bred in Brittany, France, in the 1750s via a cross of Fragaria virginiana from eastern North America and Fragaria chiloensis, which was brought from Chile by Amédée-François Frézier in 1714.[1]

Cultivars of Fragaria × ananassa have replaced, in commercial production, the woodland strawberry (Fragaria vesca), which was the first strawberry species cultivated in the early 17th century.[2]

Technically, the strawberry is an aggregate accessory fruit, meaning that the fleshy part is derived not from the plant's ovaries but from the receptacle that holds the ovaries.[3] Each apparent "seed" (achene) on the outside of the fruit is actually one of the ovaries of the flower, with a seed inside it.[3]

Contents[hide] |

History [edit]

| This section requires expansion.(November 2011) |

The first garden strawberry was grown in France during the late 18th century.[2] Prior to this, wild strawberries and cultivated selections from wild strawberry species were the common source of the fruit.

The strawberry fruit was mentioned in ancient Roman literature in reference to its medicinal use. The French began taking the strawberry from the forest to their gardens for harvest in the 1300s. Charles V, France's king from 1364 to 1380, had 1,200 strawberry plants in his royal garden. In the early 1400s western European monks were using the wild strawberry in their illuminated manuscripts. The strawberry is found in Italian, Flemish, German art, and English miniatures.[citation needed] The entire strawberry plant was used to treat depressive illnesses.

By the 1500s references of cultivation of the strawberry became more common. People began using it for its supposed medicinal properties and botanists began naming the different species. In England the demand for regular strawberry farming had increased by the mid-1500s. Instructions for growing and harvesting strawberries showed up in writing in 1578. By the end of the 1500s three European species had been cited; F. vesca, F. moschata, and F. viridis. The garden strawberry was transplanted from the forests and then the plants would be propagated asexually by cutting off the runners.

Two subspecies of F. vesca were identified; F. sylvestris alba and F. sylvestris semperflorens. The introduction of F. virginiana from Eastern North America to Europe in the 1600s is an important part of history because this species gave rise to the modern strawberry. The new species gradually spread through the continent and did not become completely appreciated until the end of the 18th century. When a French excursion journeyed to Chile in 1712, it introduced the strawberry plant with female flowers that resulted in the common strawberry that we have today.

The Mapuche and Huilliche Indians of Chile cultivated the female strawberry species until 1551 when the Spanish came to conquer the land. In 1765, a European explorer recorded the cultivation of F. chiloensis, the Chilean strawberry. At first introduction to Europe, the plants grew vigorously but produced no fruit. It was discovered in 1766 that the female plants could only be pollinated by plants that produced large fruit; F. moschata, F. virginiana, and F. ananassa. This is when the Europeans became aware that plants had the ability to produce male-only or female-only flowers. As more large-fruit producing plants were cultivated the Chilean strawberry slowly decreased in population in Europe, except for around Brest where the Chilean strawberry thrived. The decline of the Chilean strawberry was caused by F. ananassa.[4]

Cultivation [edit]

Strawberry cultivars vary widely in size, color, flavor, shape, degree of fertility, season of ripening, liability to disease and constitution of plant.[5] Some vary in foliage, and some vary materially in the relative development of their sexual organs. In most cases, the flowers appear hermaphroditic in structure, but function as either male or female.[6]For purposes of commercial production, plants are propagated from runners and, in general, distributed as either bare root plants or plugs. Cultivation follows one of two general models—annual plasticulture,[7] or a perennial system of matted rows or mounds.[8] A small amount of strawberries are also produced in greenhouses during the off season.[9]

The bulk of modern commercial production uses the plasticulture system. In this method, raised beds are formed each year,fumigated, and covered with plastic to prevent weed growth and erosion. Plants, usually obtained from northern nurseries, are planted through holes punched in this covering, and irrigation tubing is run underneath. Runners are removed from the plants as they appear, in order to encourage the plants to put most of their energy into fruit development. At the end of the harvest season, the plastic is removed and the plants are plowed into the ground.[7][10] Because strawberry plants more than a year or two old begin to decline in productivity and fruit quality, this system of replacing the plants each year allows for improved yields and denser plantings.[7][10] However, because it requires a longer growing season to allow for establishment of the plants each year, and because of the increased costs in terms of forming and covering the mounds and purchasing plants each year, it is not always practical in all areas.[10]

The other major method, which uses the same plants from year to year growing in rows or on mounds, is most common in colder climates.[7][8] It has lower investment costs, and lower overall maintenance requirements.[8] Yields are typically lower than in plasticulture.[8]

A third method uses a compost sock. Plants grown in compost socks have been shown to produce significantly higher oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC), flavonoids,anthocyanins, fructose, glucose, sucrose, malic acid, and citric acid than fruit produced in the black plastic mulch or matted row systems.[11] Similar results in an earlier 2003 study conducted by the US Dept of Agriculture, at the Agricultural Research Service, in Beltsville Maryland, confirms how compost plays a role in the bioactive qualities of two strawberry cultivars.[12] Strawberries are often grouped according to their flowering habit.[5][13] Traditionally, this has consisted of a division between "June-bearing" strawberries, which bear their fruit in the early summer and "ever-bearing" strawberries, which often bear several crops of fruit throughout the season.[13] Research has shown recently[when?] that strawberries actually occur in three basic flowering habits: short-day, long-day, and day-neutral. These refer to the day-length sensitivity of the plant and the type of photoperiod that induces flower formation. Day-neutral cultivars produce flowers regardless of the photoperiod.[14]

Strawberries may also be propagated by seed, though this is primarily a hobby activity, and is not widely practiced commercially. A few seed-propagated cultivars have been developed for home use, and research into growing from seed commercially is ongoing.[15] Seeds (achenes) are acquired either via commercial seed suppliers, or by collecting and saving them from the fruit.

Strawberries can also be grown indoors in strawberry pots.

Kashubian strawberry (truskawka kaszubska or kaszëbskô malëna)[16] are the first Polish fruit to be given commercial protection under EU law. They are produced in Kartuzy,Ko?cierzyna and Bytów counties and in the municipalities of Przywidz, Wejherowo, Luzino, Szemud, Linia, ??czyce and Cewice in Kashubia. Only the following varieties may be sold as kaszëbskô malëna: Senga Sengana, Elsanta, Honeoye that have been graded as Extra or Class I.

Manuring and harvesting [edit]

Most strawberry plants are now fed with artificial fertilizers, both before and after harvesting, and often before planting in plasticulture.[17]

To maintain top quality, berries are harvested at least every other day. The berries are picked with the caps still attached and with at least half an inch of stem left. Strawberries need to remain on the plant to fully ripen because they do not continue to ripen after being picked. Rotted and overripe berries are removed to minimize insect and disease problems. The berries do not get washed until just before consumption. They are covered in a shallow pan and refrigerated when storing.[18]

Soil test information and plant analysis results are used to determine fertility practices. Nitrogen fertilizer is needed at the beginning of every planting year. There are normally adequate levels of phosphorus and potash when fields have been fertilized for top yields. In order to provide more organic matter a cover crop of wheat or rye is planted in the winter the year before planting the strawberries. Strawberries prefer a pH from 5.5 to 6.5 so lime is usually not applied.[19]

The harvesting and cleaning process has not changed substantially over time. The delicate strawberries are still harvested by hand.[20] Grading and packing often occurs in the field, rather than in a processing facility.[20] In large operations, strawberries are cleaned by means of water streams and shaking conveyor belts.[21]

Pests [edit]

Around 200 species of pests are known to attack strawberries both directly and indirectly.[22] These pests include slugs, moths, fruit flies, chafers, strawberry root weevils, strawberry thrips, strawberry sap beetles, strawberry crown moth, mites, aphids, and others.[22][23]

The caterpillars of a number of species of Lepidoptera feed on strawberry plants.

Diseases [edit]

Strawberry plants can fall victim to a number of diseases.[24] The leaves may be infected by powdery mildew, leaf spot (caused by the fungus Sphaerella fragariae), leaf blight(caused by the fungus Phomopsis obscurans), and by a variety of slime molds.[24] The crown and roots may fall victim to red stele, verticillium wilt, black root rot, andnematodes.[24] The fruits are subject to damage from gray mold, rhizopus rot, and leather rot.[24] To prevent root-rotting, strawberries should be planted every four to five years in a new bed, at a different site.[25]

The plants can also develop disease from temperature extremes during winter.[24] When watering your strawberries, be sure to water only the roots and not the leaves, as moisture on the leaves encourages growth of fungus.[26] Ensure that the strawberries are grown in an open area to prevent fungal disease from occurring.[citation needed]

Production trends [edit]

| Country | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | 1,090,440 | 1,109,220 | 1,148,530 | 1,270,620 | 1,292,780 | 1,312,960 | n/a | n/a |

| Turkey | 211,127 | 250,316 | 261,078 | 291,996 | 299,940 | 302,416 | n/a | n/a |

| Spain | 330,485 | 269,139 | 281,240 | 263,700 | 275,300 | 514,027 | n/a | n/a |

| Egypt | 128,349 | 174,414 | 200,254 | 242,776 | 238,432 | 240,284 | n/a | n/a |

| Korea, South | 205,307 | 203,227 | 192,296 | 203,772 | 231,803 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Mexico | 191,843 | 176,396 | 207,485 | 233,041 | 226,657 | 228,900 | n/a | n/a |

| Japan | 190,700 | 191,400 | 190,700 | 184,700 | 177,500 | 182,091 | n/a | n/a |

| Poland | 193,666 | 174,578 | 200,723 | 198,907 | 176,748 | 166,159 | n/a | n/a |

| Netherlands | 39,200 | 43,000 | 42,200 | 43,000 | 42,700 | 47,000 | n/a | n/a |

| Germany | 173,230 | 158,658 | 150,854 | 158,563 | 166,911 | 154,418 | n/a | n/a |

| Russia | 227,000 | 230,400 | 180,000 | 185,000 | 165,000 | 184,000 | n/a | n/a |

| Italy | 143,315 | 160,558 | 155,583 | 163,044 | 153,875 | 150,000 | n/a | n/a |

| Morocco | 112,000 | 120,000 | 130,000 | 355,020 | 140,600 | 140,733 | n/a | n/a |

| Total world | 3,973,243 | 4,001,721 | 4,136,802 | 4,596,614 | 4,366,889 | 4,594,539 | n/a | n/a |

Domestic cultivation [edit]

Strawberries are popular and rewarding plants to grow in the domestic environment, be it for consumption or exhibition purposes, almost anywhere in the world. The best time to plant is in late summer or spring. Plant in full sun or dappled shade, and in somewhat sandy soil. The addition of manure and a balanced fertilizer aids strong growth. Alternatively they can be planted in pots or special planters using compost. Fibre mats placed under each plant will protect fruits from touching the ground, and will act as a weed barrier.

Strawberries are tough and will survive many conditions, but, during fruit formation, moisture is vital, especially if growing in containers. Moreover, protection must be provided against slugs and snails which attack the ripe fruit. The fruit matures in midsummer, and should be picked when fully ripe — that is, the fruit is a uniform bright red colour. The selection of different varietes can extend the season in both directions.[28] Numerous cultivars have been selected for consumption and for exhibition purposes. The following cultivars have gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit:-

Propagation is by runners, which can be pegged down and left to root,[35] or cut off and placed in a new position. Established plants should be replaced every three years, or sooner if there are any signs of disease.

When propagating the plant, one should avoid using the same vase for the new born, because any disease affecting the ascending plant would be propagated to the descending one. Also, when soil was previously used for strawberry cultivation, it is advisable rotating to another culture, for diseases that atack on specie might not atack another.[36]

Uses [edit]

In addition to being consumed fresh, strawberries can be frozen, made into preserves, as well as dried and used in prepared foods, such as cereal bars.[37] Strawberries and strawberry flavorings are a popular addition to dairy products, such as strawberry-flavored milk, ice cream, milkshakes, smoothies, and yogurts. Strawberries and cream is a popular dessert, famously consumed atWimbledon. Depending on area, strawberry pie, strawberry rhubarb pie, or strawberry shortcake are also popular. In Greece, strawberries are usually sprinkled with sugar and then dipped in Metaxa, a famous brandy, and served as a dessert.

Strawberry juice is a fruit juice made from strawberries. Strawberry juice or concentrate is added to cocktails, such as Minute MaidStrawberry Passion and CoolBest Strawberry Hill.[citation needed]

Strawberry pigment extract can be used as a natural acid/base indicator due to the different color of the conjugate acid and conjugate base of the pigment.[38]

Strawberries contain fisetin, an antioxidant that has been studied in relation to Alzheimer's disease and to kidney failure resulting from diabetes.[39]

Nutrition [edit]

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 136 kJ (33 kcal) |

| Carbohydrates | 7.68 g |

| - Sugars | 4.89 g |

| - Dietary fiber | 2 g |

| Fat | 0.3 g |

| Protein | 0.67 g |

| Thiamine (vit. B1) | 0.024 mg (2%) |

| Riboflavin (vit. B2) | 0.022 mg (2%) |

| Niacin (vit. B3) | 0.386 mg (3%) |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 0.125 mg (3%) |

| Vitamin B6 | 0.047 mg (4%) |

| Folate (vit. B9) | 24 ?g (6%) |

| Choline | 5.7 mg (1%) |

| Vitamin C | 58.8 mg (71%) |

| Vitamin E | 0.29 mg (2%) |

| Vitamin K | 2.2 ?g (2%) |

| Calcium | 16 mg (2%) |

| Iron | 0.41 mg (3%) |

| Magnesium | 13 mg (4%) |

| Manganese | 0.386 mg (18%) |

| Phosphorus | 24 mg (3%) |

| Potassium | 153 mg (3%) |

| Sodium | 1 mg (0%) |

| Zinc | 0.14 mg (1%) |

| Fluoride | 4.4 µg |

| Link to USDA Database entry Percentages are relative to US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

One cup (236 g) of strawberries contains approximately 45 kilo calories (188 kJ) and is an excellent source of vitamin C andflavonoids.[40][41][42]

This fruit is very low in saturated fat, cholesterol and sodium. It is also a good source of folate and potassium, and a very good source of dietary fiber, and manganese[43] One serving of about eig

yunmmy chocolate

Chocolate

Chocolate most commonly comes in dark, milk, and white varieties, with cocoa solids contributing to the brown coloration | |

| Details | |

|---|---|

| Main ingredient(s) | Chocolate liquor |